Ben Hills

When Reverend Bill Crews agreed to offer sanctuary in the grounds of his church to a small bronze statue, he had no idea what he was getting into – that he would find himself accused of inciting racial hatred and at war with an angry citizens’ group, a suburban council, a New Age church, a mob of ultra-nationalists who carry swastika flags – and even the government of Japan.

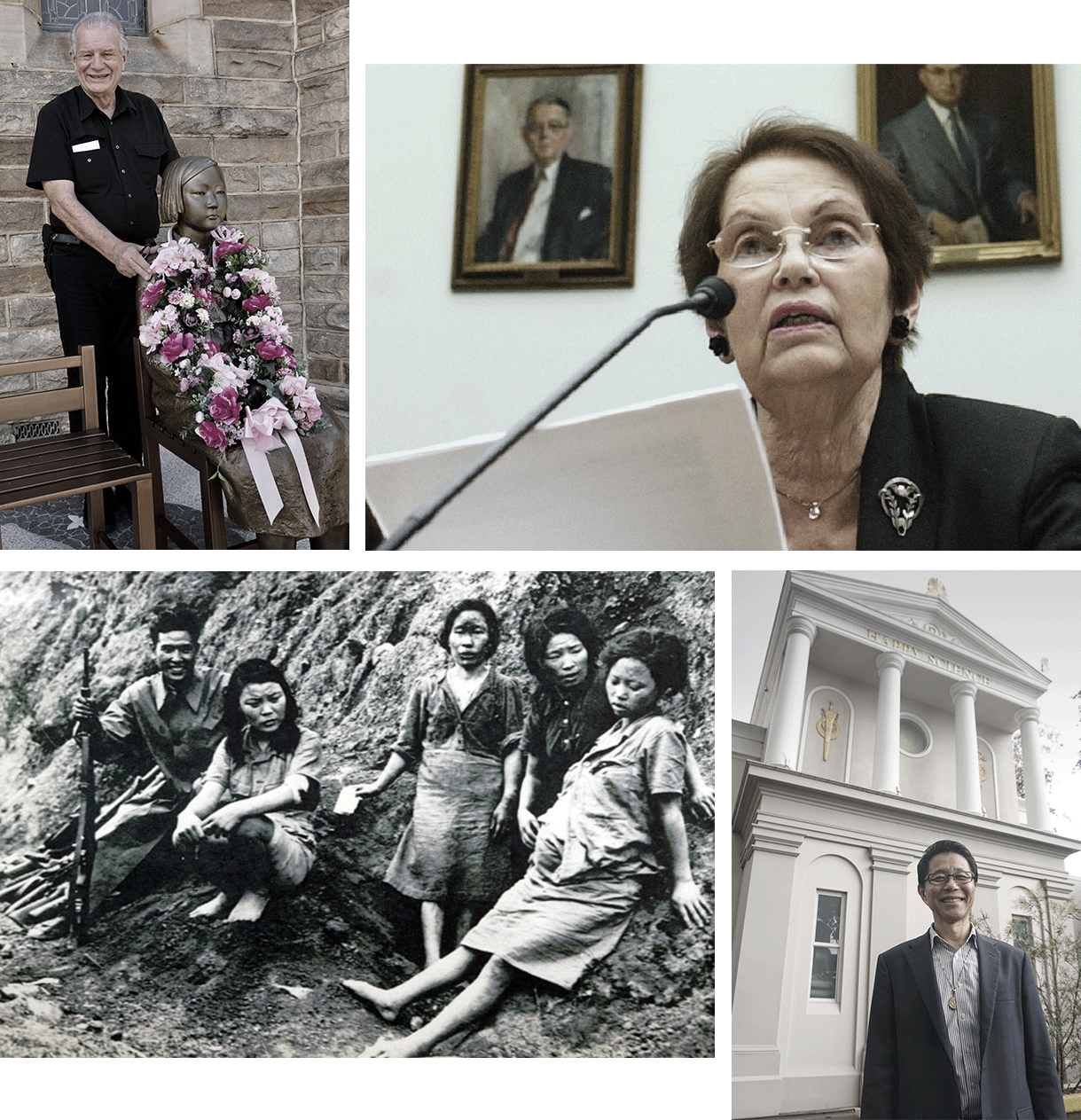

“This is what the fuss is all about,” says Bill Crews, leading me around the back of his historic brick and sandstone church at Ashfield, in a gritty stretch of Sydney’s inner west. Around us, sitting under the trees, a dozen needy-looking characters tuck into a free lunch – the Loaves and Fishes Restaurant’s popular chicken casserole.

We walk past a towering replica of the Statue of Liberty (modelled on the one erected by the students in Beijing’s Tienanmen Square in 1989 before the tanks rolled in) and there, against the wall, is a bronze statue of a young woman in traditional Korean dress seated on a straight-backed chair, with a butterfly on her shoulder and a garland of flowers around her neck, staring solemnly straight ahead. Next to her is an empty chair, symbolising women like her who never survived the war. Beside this is a simple plaque in Korean, Chinese and English which reads:

“In memory of the history of suffering endured by the young girls and women known as ‘comfort women’ who were forced into sexual slavery by the military of the government of imperial Japan…”

A tall, craggy man in his early 70s, with silver hair, a gap-toothed grin and an easy laugh, Crews is a champion of many causes, as well as the Exodus Foundation, his inner-city mission for the poor and homeless. But even he was surprised at the venom this simple, moving memorial engendered.

“Bring it on… I am having the grounds of the church landscaped and I am going to put the statue right out the front.”

In his office are two fat folders stuffed with abusive and threatening mail. He has been hauled before a government minister, and even the grandees of his own church, the Uniting Church, have tried to talk him out of it. Now he is fighting a complaint to the Human Rights Commission, made under the contentious Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act.

“You have no idea how hard they have been trying to stop it,” he says. “I have had pressure put on me from all sides. It’s outrageous. But I say ‘bring it on’… in fact, I am having the grounds of the church landscaped and I am going to put the statue right out the front” where it will be visible to everyone passing along busy Liverpool Road.

For nearly three years, Sydney’s Korean community has been battling Australian bureaucracy and a well-organised Japanese campaign to have this memorial erected. It commemorates the suffering of an estimated 200,000 women from Korea and a dozen other nations, who were conned, coerced and kidnapped to serve as “comfort women” – a euphemism for prostitutes – for the Japanese military during World War II. It has been called the greatest human trafficking crime in history.

Ostensibly the opposition to the memorial has come from a group of Japanese residents in Sydney who say that they are concerned that it will reopen old wounds and lead to prejudice against Japanese here – particularly their children who may be bullied at school. However, there are darker forces at play behind the scenes.

One of the most outspoken opponents of the memorial is the Happy Science Church, registered as a religion in Japan but denounced by some as a cult. The church, which claims 11 million followers in 100 countries, opened a branch in Australia a few years ago, a collonaded pseudo-classical temple in the leafy Sydney suburb of Lane Cove.

The founder of Happy Science, a retired salariman (Japanese corporate businessman) who uses the name Ryuho Okawa, believes that he is the reincarnation of Buddha and says he can read minds, foresee the future, and has had conversations with beings from space, as well as “the guardian spirits” of more than 1000 dead historical figures such as Margaret Thatcher, Albert Einstein, Jesus Christ and Nostradamus. The other day, he apparently had a chat with America’s first president, George Washington, who informed him that he has been reincarnated as its latest, Donald Trump.

However, it would be a mistake to dismiss the Happy Scientists as harmless nutters. Their website, texts and emissaries preach a virulent strain of xenophobic ultra-nationalism, urging Japan’s government to tear up the ‘pacifist’ article 9 of its constitution, rearm and acquire nuclear weapons in order to wage war on Korea and China. About the ‘comfort women,’ Okawa has written that their stories are “a groundless fabrication… they were prostitutes recruited by private traders’’.

Zaitokukai members are notorious for waving the Japanese ‘rising sun’ military flag and Nazi swastikas.

As for the Japanese Women for Justice and Peace, who spearheaded opposition to the Sydney memorial when the proposal was first raised in 2014, its president is Yumiko Yamamoto, who also uses the name Sakura and in fact lives in Tokyo, not Sydney. In a previous incarnation, until 2011, Ms Yamamoto was the deputy leader of a right-wing racist organisation known as Zaitokukai, and remains a supporter.

Zaitokukai members are notorious for staging noisy and sometimes violent demonstrations in Korean neighbourhoods of Tokyo and other cities, waving the Japanese ‘rising sun’ military flag and Nazi swastikas, and shouting out that the Koreans – many of them descendants of the hundreds of thousands transported to Japan as slave labour during the war – are ‘parasites’ and ‘cockroaches’ who should be killed.

Like Okawa, Ms Yamamoto is a war crime denier. “Comfort women were not sex slaves,” she said in a media interview in 2014 before heading off to the United States to lobby against the erection of comfort women memorials there. “(They were) wartime prostitutes who enjoyed spending time freely and who worked under contract for highly-paid monetary reward…”

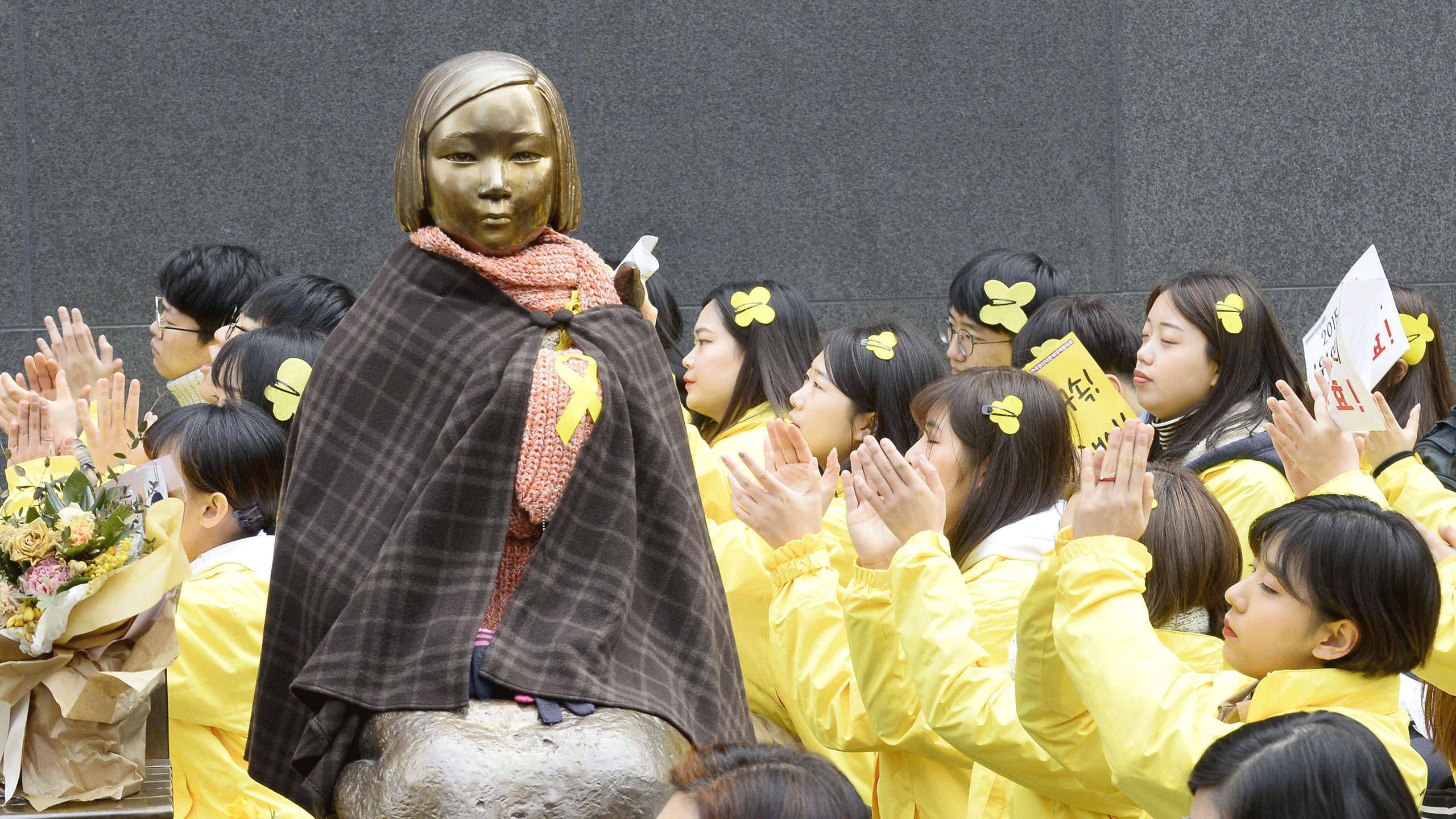

Demonstrators gather in March 2017 around a statue representing former “comfort women” installed in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, to protest against a move to remove it. Photo: Kyodo.

In a pretty green-tiled freestone cottage in the Adelaide suburb of Kingswood lives a woman who knows from first-hand experience that these are lies. Now aged 94 and a great-grandmother, Jan Ruff-O’Herne is Australia’s only known survivor of Japan’s military brothels.

Born into a Dutch family in Java – then part of the Dutch East Indies – Ms Ruff-O’Herne, her parents and siblings were interned in a prison camp near the city of Semarang when the Japanese invaded the island in 1942. Then one day a group of Japanese officers arrived and demanded that every female over the age of 17 be produced.

Along with the other women and girls Ms Ruff-O’Herne was lined up and inspected “like livestock at an auction,” she later wrote in her memoir, before 10 were led away and installed in a house that had been designated a brothel. That night, the first of a procession of soldiers raped her – a virgin barely out of her teens.

“The tears were streaming down my face,” she wrote. “It seemed as if he would never stop.” The rapes continued on an almost daily basis – she became pregnant and was force-fed an abortion drug – until the war ended and the British liberated the camp. She married one of her rescuers and they later migrated to Australia.

Ms Ruff-O’Herne kept her terrible secret for nearly 50 years – as did most of the Asian ‘comfort women’ who survived their ordeal, shamed and shunned by their communities. But then, in 1992, the first of the Korean survivors began to speak out, demanding recognition of their suffering, an apology and compensation from the Japanese government.

L-R from top: Rev Bill Crews with the statue at the Ashfield church (Photo: Ben Hills); Jan Ruff-O’Herne testifies in 2007 to the US House Foreign Affairs Committee in Washington (Photo: AP Photo/Dennis Cook); four Korean ‘comfort women’ liberated at the end of WWII (Photo: US National Archives); Happy Science’s Sydney Head Minister Hironobu Sunada at his church (Photo: Ben Hills)

Their pleas were ignored by Japan’s right-wing Liberal Democratic government which dismissed their claims, offering a bewildering variety of alibis: the women were volunteers; they were well paid and well treated; the Japanese military had nothing to do with it, it was all handled by civilians; the numbers were exaggerated; the 1965 treaty under which Japan paid Korea $US800 million compensation was final settlement for any war damages; and even ‘the Koreans had comfort women too’.

Jaws dropped when, in 1992, Japan’s Justice Minister, Shigeto Nagano, denounced the women as ‘licensed prostitutes’… and, for good measure, enraged China by declaring that the atrocity known as the Rape of Nanking – in which as many as 300,000 Chinese soldiers and civilians were slaughtered by Japanese troops – never occurred. This was seen by the rest of Asia as war crime renouncement on the scale of Holocaust denialism.

“The world wasn’t listening to them,” said Ms Ruff-O’Herne. “I got so annoyed I thought ‘If a European woman speaks out, the world is going to listen’.” And so she did, embarking on a mission that took her to five countries – including Japan – that finally helped persuade the world that industrial-scale rape had occurred, and that it constituted a war crime.

In 1996, the United Nations Human Rights Commission’s Special Rapporteur, Radhika Coomeraswamy, conducted an extensive investigation – including interviewing surviving comfort women and inspecting such historical records as had survived Japan’s organised war’s end arson – and reported:

“…the phrase ‘comfort women’ does not in the least reflect the suffering, such as multiple rapes on an everyday basis and severe physical abuse that women victims had to endure during their forced prostitution and sexual subjugation … the phrase ‘military sexual slaves’ represents a much more accurate and appropriate terminology.”

Although she was too frail to travel to Sydney last year for the official unveiling of the memorial, Ms Ruff-O’Herne has put her moral weight behind it. This is what she wrote to me:

“The Japanese are a very proud people and they have never acknowledged their war crimes. The abuse I suffered at the hands of the Japanese during World War II has affected me all my life…. This statue is a reminder that these terrible war crimes against women will never happen again.

“Ex-servicemen are given war medals; the comfort women deserve some recognition also. This statue is to honour the comfort women – they were war victims, they suffered so much. Together with my comfort women sisters I want to say ‘Thank you’ for the statue.”

The Japanese PM offered his “heartfelt apology and remorse to all who, as comfort women, experienced much suffering and incurred incurable psychological and physical wounds”.

The first memorial to the comfort women opened in 1992, the Nanum Jip (House of Sharing), a small museum about an hour’s drive out of the South Korean capital of Seoul, which also incorporates a refuge for some of the elderly survivors. I visited there the following year, after Mr Nagano’s outburst, to try to get to the truth of the matter for the Fairfax newspapers. I was deeply moved by the stories the women, then in their 60s and 70s, told.

Since then, nearly 100 memorials, statues, plaques and museums have opened around the world, over the strident opposition of the Happy Science Church, Zaitokukai and a dozen other ad hoc Japanese protest groups – as well as the Japanese government. There is a plaque in Manila, a museum in Taipei, and the Chinese have opened an exhibition in Nanking, in a building which once housed the oldest and largest of the military brothels. In 2015, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors approved the erection of a statue in a Chinatown park which will be the ninth such memorial in the US.

There are about 40 of these memorials around Korea, the most controversial of which is in Seoul. It has been placed directly opposite the Japanese Embassy. Surviving comfort women and their supporters regularly gather there to demand an apology, acknowledgement and compensation from the Japanese government. In December, ignoring official protests from Japan, the Koreans doubled down, erecting a replica opposite the Japanese Consulate-General in Busan, South Korea’s second city. In protest, Japan recalled its ambassador.

Not all Japanese, however, are opposed to recognising the comfort women. There have been exhibitions with photographs, films and testimony honouring them in places as diverse as Kochi City, Nagasaki, Okinawa and Tokyo’s Shinjuku district – and in 2015, 16 Japanese historical societies signed a petition calling for the true story to be acknowledged in history books.

In December 2015, more than 20 years after the first comfort women stepped out of the shadows, the governments of South Korea and Japan reached what they said was a “final and irreversible” agreement settling the issue. The Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, offered his “heartfelt apology and remorse to all who, as comfort women, experienced much suffering and incurred incurable psychological and physical wounds” – plus $11.5 million in compensation – on condition the statue be removed from opposite the embassy.

Unfortunately no one had consulted the surviving comfort women – now believed to number fewer than 40 – about this deal. The offer was promptly rejected, the statue remained where it was, and the demonstrations resumed. Now, with the then South Korean President Park Geun-hye sacked and indicted for bribery, and her likely successor, Moon Jae-in, promising to tear up the deal, there is no resolution in sight.

“Good afternoon, cockroaches… we are demonstrators from the All-Japan Committee to Expel Insects that are Noxious to Society.”

So, in view of this history, it should have come as no surprise that when Sydney’s Korean community began to raise money for a statue to be erected in Ashfield, one of Australia’s most multicultural constituencies where about a quarter of the population is Korean or Chinese – they discovered they were up against a formidable opposition, a group called Japanese Women for Justice and Peace.

It was Tessa Morris-Suzuki, the professor of Japanese history at the Australian National University, who first alerted people to the fact that there was more to the opposition than met the eye:

“The AJCN [Australia-Japan Community Network] may indeed include Sydney-based Japanese parents who believe that they have something to fear from the statue,” she wrote on the online academic website Inside Story. “But the claim that the group’s campaign is simply a grassroots appeal against ethnically motivated hostility is, to say the least, disingenuous. Australian groups including the Uniting Church, Strathfield Council… and the Human Rights Commission… have a right to know the backstory.”

In fact the founding force behind the opposition to the statue is Tokyo-based Yumiko Yamamoto, who is well-known in Japan as an anti-comfort women campaigner and former vice-president and secretary-general of Zaitokukai, an organisation dedicated to combating what members claim are privileges enjoyed by Japanese of Korean ancestry. Vice News has described them as “J-racism’s hottest new upstarts”.

Zaitokukai’s tactics include staging noisy demonstrations in ethnic Korean neighbourhoods, carrying ‘rising sun’ flags and swastikas and hurling abuse. Opposing ‘anti-Nazi’ protesters frequently clash with them in violent confrontations, some of which are posted on YouTube. Japan’s Asahi newspaper reported on one in 2013:

“In early afternoon on a Sunday in March, Makoto Sakurai (Zaitokukai’s chairman) was spewing words of hate over a loudspeaker from the lead car of a convoy of vehicles in Tokyo’s Shin-Okubo district. ‘Good afternoon, cockroaches… we are demonstrators from the All-Japan Committee to Expel Insects that are Noxious to Society… Let’s tie ethnic Korean residents in Japan to (North Korea’s) Taepodong (ballistic missiles) and fire them into South Korea’.”

Zaitokukai has been convicted at least twice for its racist rants. Last September, in the Osaka District Court, it was ordered to pay $9000 for defaming Lee Shin-hye, a 45-year-old freelance writer whom it called “a Korean crone” online and over loudspeakers after she had the temerity to write critically of them. In July 2014 the Osaka High Court fined Zaitokukai $140,000 for disrupting classes at the Kyoto Korean School by using loudspeakers to amplify insults, such as: “Cockroaches, maggots go back to Korea.”

Hironobu Sunada told me, “They were not sex slaves, they were prostitutes… they were not forced by the military, they needed the money.”

Although Yamamoto resigned from the organisation in 2011, she said in her resignation letter that she remained a supporter: “I pray from the bottom of my heart for the future development of the association and for the continued success of every branch, operation and member.” She could not be contacted for further comment.

When an application from the Korean community to have a comfort women statue erected in Croydon Park came before Strathfield Council, the councillors were faced with a hostile barrage of opposition. AJCN – many of whose supporters live in Japan and use .jp email addresses – had organised an online petition, which it claimed had attracted 16,000 signatures, and when the council met in 2015 to vote on the issue about 120 protesters packed the chamber. The AJCN rejoiced online when the council unanimously rejected the application.

The council was somewhat surprised to find that the AJCN had been joined by an unexpected ally in its fight against the memorial – a New Age church. One of the speakers chosen to put the ‘no’ case to the meeting was Brian Rycroft, a spokesperson for the Happy Science Church.

Like Yamamoto, Rycroft doesn’t live in Sydney – he is a South African-born resident of Japan’s Chiba prefecture and works for the Happy Science University. He seems to have been a kind of roving ambassador for the church, having bobbed up in 2012 in the Ugandan capital of Kampala, where he booked the national stadium for a Happy Science rally. Ugandan athletes were evicted and had to complete their time trials at a rubbish dump – a humiliation which they later blamed for their failure at the London Olympics.

So what is Happy Science? It was founded in 1986 by a Shikoku-born former employee of a Japanese trading company named Takashi Nakagawa, who became convinced he was the reincarnation of Buddha and adopted the “holy name” Ryuho Okawa. As one of his many divine gifts, Okawa claims to be the world’s most prolific writer – the walls of the reception-hall of the Happy Science temple are lined with copies of 2500 books with his name on the cover, many of them transcripts of his conversations with figures such as the prophet Mohammed, Japan’s wartime leader Emperor Hirohito, and the late North Korean dictator Kim il-Sung. All of them, he says, speak contemporary Japanese… although with an accent.

His wife, Kyoko, believes she is the reincarnation of both Florence Nightingale and the Greek Goddess of Love, Aphrodite. She was one of the candidates of Happy Science’s political wing, the Happiness Realization Party, at the 2009 Japanese elections, running on a platform which included doubling Japan’s population to 300 million, space shuttle flights between Japan and the United States, and rearming the country for a war with Korea and China.

Left: Tetsuhide Yamaoka (Photo: ABC News), below Zaitokukai protesters in Osaka, Japan (Photo: Kyodo News).

Centre: The comfort women statue near the Japanese consulate in Busan, South Korea (Photo: Kyodo News).

Right: Yumiko Yamamoto (Photo: YouTube) above Zaitokukai protesters in Osaka, Japan (Photo: Kyodo News)

I visited the church’s Sydney temple to ask Happy Science’s ‘Head Minister’ in Australia, Hironobu Sunada, why his church opposed the Korean community’s attempts to commemorate the comfort women, and why he had taken it on himself to visit Bill Crews to try to talk him out of his offer to host the statue at his church after Strathfield Council rejected it.

The ‘comfort women,’ he told me “… are liars… it is a made-up story. They were not sex slaves, they were prostitutes… they were not forced by the military, they needed the money.” When I asked him how he knew this, he referred me to the teachings of Okawa, whom he said was “our father in heaven” and offered me three of his books and a tour of his hall of worship, dominated by a two-metre-tall statue of Happy Science’s God, El Cantare, a dazzling figure coated in gold leaf.

When I read some of Okawa’s writings, it became clear why his followers disbelieve survivors like Jan Ruff-O’Herne. Okawa has interviewed the “guardian spirits” of some of the comfort women. And they have confessed to him that they were lying about their experiences to try to get compensation from Japan. “The Japanese soldiers were wonderful,” one of them told him. “The Korean administrators were the ones that engaged in the violence.”

Bill Crews was in England when he heard a BBC news broadcast about Strathfield Council’s rejection of the statue – the story made news around the world. “I was absolutely outraged,” he says. ‘’How dare they deny people the right to know how women were treated during the war?” As soon as he got back to Australia he contacted Vivian Pak, a Strathfield solicitor who is co-chair of Korean Women for Peace and Justice, the organisation which has been lobbying for the statue.

“He’s a wonderful guy, so full of confidence,” she says. “He said that he would go all the way and so we accepted his offer.” As well, the spot behind the church designated for the statue is covered by several CCTV cameras – essential security, says Ms Pak, since the statue in Seoul has been attacked with a sledgehammer, and one in the United States was mocked by a man who pulled a brown paper bag over the statue’s head and posted a picture online.

“They were afraid it would stir up ethnic hatred and Japanese people would not be able to walk down the street because Koreans might bash them up.”

A Korean businessman offered to pay for the casting of a bronze replica of the statue that stands in Seoul, and local Korean Australians raised funds for transport, insurance and an opening ceremony – all told, it cost a sizeable $70,000. But once again a campaign to ban the memorial swung into action. “We were fighting, fighting, fighting,” Ms Pak says.

This time, opposition to the statue was spearheaded by the AJCN, whose president is the Tokyo-based Hideyuki (“Hardi”) Odaka, who says he uses the pseudonym ‘Tetsuhide Yamaoka’ “for privacy reasons”. Once again the emails began to pour in, and the council – Canterbury-Bankstown this time – was lobbied to prevent an unveiling ceremony. These were some of the comments made by supporters of AJCN in emails to Bill Crews: “The comfort women were simply prostitutes owned by Korean traders.” “The comfort women issue is the Koreans sordid intention to cadge to Japan.” “(They were) professional camp followers.” “They lived in near luxury in Burma.” “They earned ¥1500 a month when ¥5000 would buy a house in Tokyo.” “They were able to buy cloth, shoes, cigarettes and cosmetics.” “The comfort women were treated and paid well—they were not slaves.” “The comfort women issue is an imaginary narrative.”

The big guns were brought out. Last July, Bill Crews was summoned to a meeting with John Ajaka, then the NSW Minister for Multiculturalism, and Masato Takaoka, the Japanese Consul-General in Sydney. Ironically it was the same John Ajaka who in 2015 awarded Bill Crews the NSW Human Rights Award which hangs from his office wall, declaring: ‘’Rev Crews is a passionate campaigner who exemplifies compassion.”

At the meeting, they urged him not to go ahead with hosting the statue because “they were afraid it would stir up ethnic hatred and Japanese people would not be able to walk down the street because Koreans might bash them up”, Crews says. “It’s complete nonsense.” Asked why the Japanese government would want to intervene in an Australian domestic issue, a spokesman for Mr Takaoka responded: “We have no comment on the said meeting.”

‘Tetsuhide Yamaoka’ said he had heard of a Japanese family whose daughter had been served boiling water at a Korean restaurant and burned herself.

‘Yamaoka’ threatened that if the statue – with its plaque referring to ‘Japanese sexual slavery’ – were installed, he would lodge a complaint with the Human Rights Commission that it constituted a breach of the Racial Discrimination Act’s controversial Section 18C, which makes it an offence to “offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate” anyone because of their “race, colour or national or ethnic origin.” And last December a complaint was lodged against the Uniting Church.

I asked ‘Tetsuhide Yamaoka’ – who spoke in Tokyo last year on the same stage as Yamamoto at a gathering to condemn Prime Minister Abe’s 2015 apology to the comfort women – whether he found it ironic that his organisation, which reviles Korean sex slaves as ‘paid prostitutes’, should itself claim to be the victim of racial vilification.

He said that he had lodged the complaint because he feared that Japanese in Sydney would be subjected to “racial bullying” – as had occurred in the United States – if the statue and its plaque continued to be on display. When I asked whether, in the six months since it had been installed behind the church, any “racial bullying” had in fact occurred, he said that he had been told of a Japanese family in Sydney who went to a Korean restaurant and their daughter had been served a glass of “boiling” water and a straw and burned herself.

I also asked him whether, if the Human Rights Commission dismissed his complaint, he would accept the result and he said: “No, I will not.” And, true to his word, when his original complaint against the Uniting Church was dismissed in January Yamaoka (using his real name of Odaka) lodged a second complaint — a date has to be set for a “conciliation hearing”.

As for Bill Crews, he says that he is not going to be intimidated by the complaint – or anything else. In fact, he seems to thrive on conflict. Last year, on the birthday of his friend the Dalai Lama, he let it be known that he intended to fly the ‘snow lion’ flag of the free Tibetan movement from his church.

“Some Chinese threatened to pelt the church with eggs if I did,” he laughs. “So I flew two flags. Nothing happened.”

Publishing Info

Pub: SBS Online

Pub date: 31 March 2017