Ben Hills

When Delwyn Richards hauled herself out of bed to answer a bang on her front door at 11 on a Sunday night she knew it was not going to be good news. But nothing could have prepared her for the shock of finding two grim-faced police officers standing there. “It’s about my son,” she thought as she showed them into the lounge-room. “He’s been in an accident. Oh God, he’s not ….”

The police were on what they call a death-knock, but it wasn’t about Alec, her 20-year-old who had just left home to live in Sydney. If anything, the news was even more terrible. Her beloved nephew Darren had been in a car accident – he and his entire family had been killed, with the exception of the youngest, a seven-year-old boy who was fighting for his life in hospital.

Delwyn rushed to the bedside of the little boy, Benjamin, who had been extricated from the wreckage of the car and helicoptered to Westmead Hospital with a damaged spine, a broken leg and serious internal injuries. As his next-of-kin – other relatives were overseas – she authorised surgery, after which he was placed in intensive care, in an induced coma.

But nothing could be done for the rest of the family, who had been pronounced dead at the scene: Darren Milne, who was 42, his Mexican-born wife Susana Estevez Castillo, 39, and their older son Liam, 11. It was discovered later that Susana had been 29 weeks pregnant, expecting their third child.

Susana Milne and her sons Liam (right) and Benjamin enjoying their last beach holiday a few weeks before the fatal crash (Photos: Facebook).

“I couldn’t believe it at first,” says Delwyn, pouring a pot of herbal tea in the kitchen of her house on a hill in the seaside Newcastle suburb of Redhead. “In fact I’m still trying to come to terms with it… How could a man like Darren have done such a thing?”

Because, as the months went by and forensic police delved more deeply into the circumstances, it became increasingly apparent that this was no accident. Last May, a year after she lost her nephew and his family, Delwyn sat in shock in the modern little court-house in the NSW Central Coast town of Wyong, listening to police describe how Darren had spent months meticulously planning their deaths.

Computer files found at his home showed that he had carefully reconnoitred roads through heavily-wooded parts of the countryside north of Sydney, videoing likely spots to stage the crash with a dashboard-mounted camera. Eventually he chose a straight stretch of road, near the sleepy village of Fountaindale, where a large gum-tree stood conveniently close to the roadside. He was seen taking a photograph of the tree, and he used a rostered day off work to do as many as 10 practice runs past it.

Watch video from Darren Milne’s dashboard-mounted camera. (Video: Coroner’s Court)

A methodical man, Darren decided to leave nothing to chance. Police dissecting the mangled remains of the car discovered that, using his skills as an electrical engineer, he had improvised two petrol bombs and wired them to an electrical circuit designed to explode on impact. Fortunately for Ben it failed to go off, otherwise he would have been incinerated, along with his brother and his parents.

Why, everyone attending the inquest must have been wondering, would an apparently normal, hard-working, comfortably-off family man decide one day to obliterate himself and his family? No-one around him, not his friends, not his work-colleagues, not Delwyn nor other relatives noticed any sign of stress or distress – let alone a mental illness dangerous enough to drive him to his death.

The answer appears to lie in an unlucky genetic turn of fate, an inherited condition which wasn’t described until the end of World War II, wasn’t named until the 1970s – and is still much of a mystery, unknown to the public at large and even to many in the medical profession. Both Darren’s children suffered from what is now called Fragile X Syndrome.

To everyone who knew him, Darren Milne had the world at his feet – a senior position as an engineer at Ausgrid (the poles-and-wires company which owns and operates the electricity distribution network in the Sydney area), a loving marriage, a couple of kids, a house in the leafy Sydney suburb of Ryde.

“They were just a normal, happy couple,” says Delwyn, who had the family to stay with her two or three times a year for birthdays. “Darren was a great dad.”

“He didn’t talk much about his personal life, but he was very intelligent, very knowledgeable about his work,” says his supervisor at Ausgrid’s depot in inner-Sydney Zetland, John Vaartjes. “He was becoming quite a technical guru.”

Born in Geelong, his family had moved to Sydney when Darren was at school, and he completed his degree in electrical engineering at Sydney University. He met Susana, the woman who would become his wife, on a Contiki tour of Europe, and after a whirlwind romance they married in her home-town of Villa de Arista, in the central Mexican state of San Luis Potosi in 2002.

For the rest of Liam’s short life they would be taking him to a succession of doctors and therapists, in a vain search for help with his delayed development, his lack of speech, his acute anxiety, his sleep disturbances.

Swarthy and vivacious, Susana came from a wealthy family and was studying international economics and trade at San Luis Potosi’s university. However, despite some family misgivings, the following year she and Darren decided to move to Sydney where they were ecstatic to discover that Susana was expecting their first child. Ecstatic, but a little apprehensive.

Susana was aware that she had “a family history of individuals being mentally impaired,” according to a letter she and Darren later wrote complaining that Royal North Shore Hospital, where they attended their first antenatal clinic, had failed to check for Fragile X before the child was born. The hospital denied liability.

According to the letter they had made a point of mentioning this to the staff, but they were reassured that there was nothing to be concerned about. There was no attempt to establish an inheritance pattern or conduct genetic testing or any other medical investigation.

Not long after Liam’s birth they began to worry that something was not quite right – the child’s muscle tone was poor, and he was very restless at night, in spite of Susana checking them both in to a Tresillian parenting centre for a week. However the nurses at the postnatal clinic she attended still maintained that there was no cause for alarm. It wasn’t until Liam was nearly four and still unable to speak a word that his pre-school teacher raised a red flag and they were referred to a pediatrician.

“It came as an absolute bolt from the blue when they told me the boys had Fragile X Syndrome. I said ‘What’s that?’”

The diagnosis? Autism spectrum disorder. It was a shock to Darren and Susana, and for the rest of Liam’s short life they would be taking him to a succession of doctors and therapists, and treating him with a variety of drugs, in a vain search for help with his delayed development, his lack of speech, his acute anxiety, his sleep disturbances and other issues associated with autism.

However, unaware that it was a misdiagnosis, and not believing that autism could be hereditary, they decided to have another child, and in 2007 Ben was born. They were shocked to discover as the months went by that he, too, had some worrying symptoms, although they were less severe than his older brother’s. Eventually they were sent to a specialist who suggested genetic testing. Liam was eight and Ben was four before they discovered the truth.

“They seemed to be coping fine. No-one had any idea what was going on.”

Delwyn, who last saw them together as a family on Susana’s birthday, five months before the car crash, says: “They were the same as usual. Ben was fine, but Liam was very affected, very noisy, very disruptive. It came as an absolute bolt from the blue when they told me the boys had Fragile X Syndrome. I said ‘What’s that?’”

Like most people, Darren and Delwyn had never heard of the condition, even though about 100,000 Australians carry the genetic defect, and between 5400 and 8600 people have the full-blown condition – twice the number who suffer from far more familiar – and far more generously-funded and government-supported – inherited conditions such as cystic fibrosis.

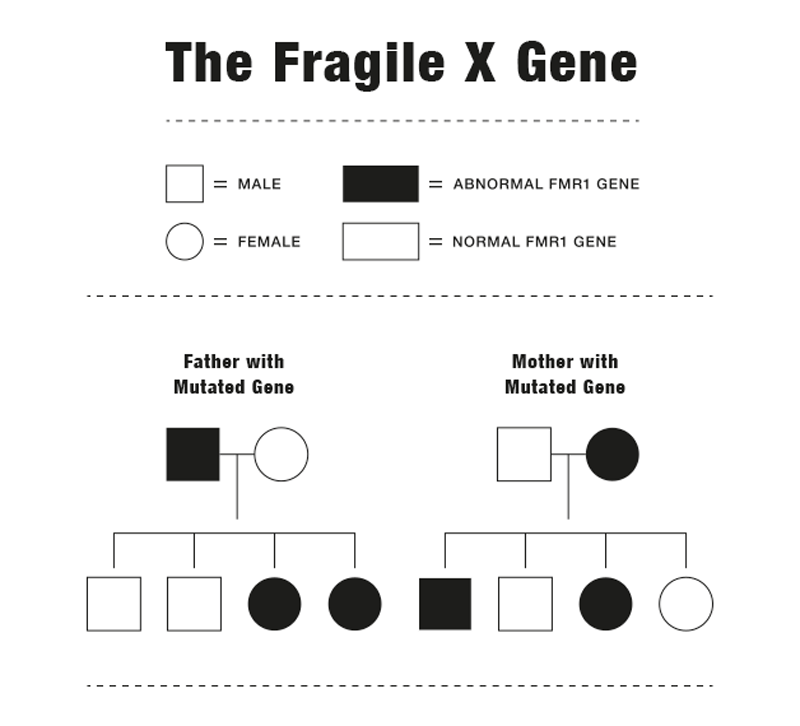

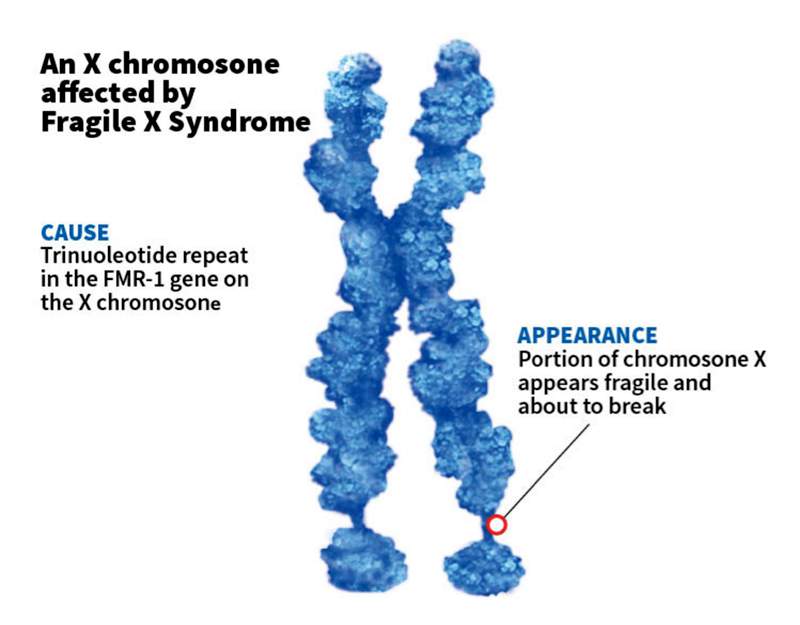

Caused by a mutation of a gene on the X chromosome, women like Susana are more often the unknowing symptom-free carriers and boys like Liam and Benjamin are more often severely affected. It is the most common inherited cause of autism, and may cause a bewildering array of other physical and intellectual symptoms which often lead to misdiagnosis.

The syndrome was named for the appearance of the affected X chromosome. (Illustration: Scientific American).

In spite of this, in the winter of 2014 Darren and Susana decided to have a third child, much to the surprise of their friends. They went to extraordinary lengths to make sure that this time the new baby would not inherit Fragile X from his mother. According to evidence at the inquest, they endured no fewer than seven IVF cycles (at $10,000 a time) before the pregnancy was successful, each time genetically testing the embryo before implanting it in Susana’s womb to make sure it was free of the mutation.

Police speculated at the inquest that they wanted to have an able-bodied sibling for Liam and Benjamin so that the boys would have someone to care for them after their parents died.

Whatever the strains it placed on their relationship – and they must have been considerable – to the outside world Darren and Susana were a happy couple and loving parents. “They seemed to be coping fine,” says Delwyn. “No-one had any idea what was going on. No-one could believe it until it all came out at the inquest.”

“It’s not worth it, neither of us have the skills to make it work. Too much is conspiring against us.”

What came out was that Darren, the capable, coping professional, had been seeing a psychiatrist, Dr Jason Pace, on and off since 2007 and was being treated for “some kind of depression or ADD attention deficit disorder” which later became major depression – presumably brought on by the burden of caring for the two boys.

Money certainly wasn’t the problem as it is with many Fragile X parents – an actuarial study has found that it costs an additional $200,000 to raise a child with this disability. But Darren had $30,000 in the bank when he died, and Susana had $200,000-worth of investments in her own right.

From the evidence it seems as though Darren began planning their deaths the previous winter when he stopped seeing the psychiatrist.

On his iPad recovered from the wrecked car, police found a note dated September 20, 2014 – four months before the crash – headed ‘PLAN –STAGE 2’. It read:

“It’s not worth it, neither of us have the skills to make it work. We have both given it our best shot over a long period of time.

There is too much conspiring against us.

God got the calculation wrong, it’s that simple.

L & B are both happy, B doesn’t yet know, it is a good time to go. It is only going to get tougher as time goes on.

We have been completely S’d over, maybe we can stop it happening to someone else.

They are going to have to manage ADD + Diabetes, it is going to be too much. They need to exercise & manage their health, it is going to be hard to see this fail.

Things are going to get progressively harder for Ben. He hasn’t seen any malice or bullying yet, but it is coming.”

From video recordings recovered from his computer, police were shocked to discover that he had been reconnoitering suitable places in the bush near Sydney to stage the crash for several weeks – the Old Pacific Highway at South Maroota, the Northern Road at Penrith, Wiseman’s Ferry Road between Spencer and Mangrove Mountain, and Sackville Ferry Road.

The spot he eventually chose, Enterprise Drive, Fountaindale, on the NSW Central Coast 60 kilometres north of Sydney, seemed ideal. It was a straight stretch of thinly-trafficked road where he could build up speed, and there was a solid gum-tree close to the left-hand verge into which he planned to hurtle his grey Toyota Corolla.

Not satisfied that the impact of the car would kill everyone, he next improvised two petrol bombs out of aluminium canisters which he filled with half a litre of fuel each, and wedged behind the headlights. He connected these to the car’s battery with an elaborate electrical circuit which also included three 12 volt batteries of the type used to power ride-on children’s toys. As a final touch he planned to disable the driver’s airbag in the car – the only one fitted in this model – which would later fail to deploy on impact.

(top) The elaborate electrical circuit Milne built to detonate the bombs.

(right) One of the petrol bombs Milne installed in the car.

(left) The wreckage of the car after Darren Milne drove it into a tree at 85 kph.

(Photos: Coroner’s Court)

The Christmas before the crash Darren claimed some long service leave from Ausgrid, and took the family for a six-week beach holiday. It was the last they would ever enjoy together. If it was intended to repair the relationship it was not a success – Susana’s family, with whom she was communicating via Skype, said that she appeared “… upset and depressed with the pending baby, and she was having difficulties communicating with Darren.”

In what police called his iPad “suicide notes” he describes his preparations for the final, fatal drive with blood-chilling attention to detail:

“From this point on I need to be totally focused, forget everything else. …. Finalised medical records disk & leave copies— letter to HGA — correspondence. Start cleaning stuff up.

“It was just bang, straight into the tree, no brake lights.”

Take DVR out of the car so as to not raise suspicion. Carry out recon after daylight savings, full day on RDO — look at old Pacific hwy to Central Coast — stay until dark, practice at least 10 times — memorise all road markers, learn the road backwards.

Copy all work personal stuff to portable disk. Start taking personal stuff home. Leave credit cards well in credit. Leave enough money in … phone.”

But, at work Darren appeared to be his normal, competent, relaxed self. “There was no sign of depression, none of us had any inkling that he was contemplating anything,” says John Vaartjes. The last conversation they had, three days before the crash, Darren was giving him some investment advice.

The following day, a Friday, Darren dressed for work and set off for Ausgrid. However, unbeknown to his family, he had a rostered day off. Instead of going to the Zetland depot he drove to Fountaindale and spent the afternoon driving his car in practice runs along the stretch of Enterprise Drive which he had chosen.

Two days later, February 1 2015, a sunny Sunday morning, Darren Milne loaded his family into the car for their last outing. Delwyn is certain he would not have told Susana or the children what he was planning – why would they have got in the car if he had?

He drove from Ryde up the Pacific Highway and then turned off near Tuggerah Lake onto Enterprise Drive just after midday. A local diesel mechanic who was following the Toyota said the car accelerated to about 85 kilometres an hour on that straight stretch of road before leaving the bitumen, as if taking an off-ramp from a freeway, and ploughed into the tree. “It was just bang, straight into the tree, no brake lights, ”he told the inquest. “My first thought was ‘He’s done that on purpose.’”

By the time the emergency services arrived Darren was dead and Susana was dying. Liam died of a heart attack in the ambulance, and the sole survivor, Ben – saved by having been strapped into a five-point safety harness – was flown to Westmead Hospital for emergency surgery.

“We thought we knew Darren, but obviously we didn’t. It was a bit of a Jekyll and Hyde story.”

Police were baffled right from the start at how the ‘accident’ could have happened on a fine day on a clear stretch of road. Inspector Colin Lott of the Tuggerah Lakes Local Area Command who took charge of the scene, told reporters: “It hit the tree at full speed. It was not a savage turn and the car was only a few metres off the road. Most likely the driver turned to speak to the children.”

It would be several weeks before they discovered the shocking truth.

Until Darren’s father John turned up at the depot to collect a condolences book which his son’s colleagues had compiled, everyone had thought stories that his death was a suicide were “rubbish, a media beatup.”

“We thought it was just a tragic accident until he told us that it wasn’t,” says John Vaartjes. “There was a stunned silence. No-one could believe it. We thought we knew Darren, but obviously we didn’t. It was a bit of a Jekyll and Hyde story.”

In the Wyong court house last July the coroner, a country magistrate named David Day, delivered a harsh judgement which concluded:

“It is unusual for a Coroner to comment on the conduct of a person who has taken their own life. Two other lives were taken by him and the conduct of Darren Milne should attract more than the usual disapproval attached to murder and suicide..

“He made assumptions about the boys’ lives. He disregarded the boys’ fundamental human rights. He disregarded potential advances in medical science potentially beneficial to the boys.

“He assumed successful execution of his plan without regard to the possibility that the front seat occupants, he and Susana, may not survive but that one or both the rear seat passengers would survive, terribly injured, severely disabled…. or worse, be conscious, trapped inside the cabin when the car caught fire.

“He disregarded the excellent services available to persons contemplating self-harm. He had a psychologist (but) dropped out of treatment…. Suicide is a preventable death, and in this case the deaths of Liam and Susana were preventable.”

However, one person in court that day was not satisfied with the scale or the scope of the inquest. He is Bruce Donald, a lawyer who is the father of a young woman with Fragile X Syndrome and a former treasurer of the Fragile X Association of Australia, a small charity based in Sydney which counsels and advocates for families affected by the condition.

Fragile X was only mentioned in passing in the coroner’s findings.

Donald attended the inquest, and was surprised and deeply disappointed that no evidence was called about the family’s struggle with Fragile X. Only four witnesses were called (two police and two bystanders) in a hearing that lasted about four hours – and Fragile X was only mentioned in passing in the coroner’s findings.

He points out that coroners have a duty – as Mr Day himself said – “… to find out what happened to the deceased (to) reduce recurrence where possible.” For instance, in another recent family murder/suicide tragedy at Lockart near Wagga Wagga in 2014 – in which a farmer killed his brain-injured wife and three children before turning the gun on himself – the coroner devoted four days to taking evidence from more than a dozen witnesses, including relatives, a forensic psychologist and the woman’s carer, to try and understand the underlying cause of their deaths.

Donald says that he also expected a broader examination of the failure of the hospital system, first to test Susana for Fragile X, in view of her family history, in 2003 when she was expecting her first child. And then, when Liam displayed serious symptoms, its failure to test him in 2007/8 when Fragile X should have been well-known to paediatric specialists. Correct diagnosis would have alerted them to the risk involved in a second pregnancy, and would have enabled them to seek therapy for both boys years earlier.

It is far from the first time this has happened – the association knows of families who have inadvertently had as many as five children with Fragile X before the condition was identified. Two families, one in Melbourne and one in Newcastle, have taken legal action against a hospital and the fertility clinic Genea (formerly Sydney IVF) for failing to identify and warn them about the condition.

In the Newcastle case, a woman named Leighee Eastbury claimed that genetic screening by Genea failed to identify her as a Fragile X carrier and she gave birth to two boys with intellectual disabilities and behavioural problems requiring high levels of ongoing care. In Melbourne a couple is suing the Royal Melbourne Hospital for failing to diagnose Fragile X in their first child – they subsequently had a second child with serious symptoms of the condition.

Both Genea and the hospital deny liability and the cases are ongoing.

This is why the association has been lobbying for years for Fragile X to be added to the list of inherited ailments for which all states offer free testing of newborn babies. A drop of blood is taken from the heel of the baby and sent for screening for (in NSW) five conditions, including cystic fibrosis. Fragile X is not one of them.

“If Fragile X had been discovered early on, this tragedy may never have happened,” says Donald.

The only positive note on which to end this terrible tale is with Ben, the surviving boy, who is now nine years old, and living with relatives of his mother in the United Kingdom.

The day after the accident his aunt, Elena Estevez and her husband Eros Santi, flew out from London to be by his bedside at Westmead Hospital as he hovered near death. Days turned to weeks as doctors struggled to save him, but eventually he regained consciousness and work began on his rehabilitation.

Parents from his school, Truscott Street Public School in North Ryde, rallied round to raise $38,000 to pay for a full-time carer. It took three months, but by the end of April doctors took off his back brace, and by the middle of May he stepped out of his wheelchair.

The last word from Elena to a local newspaper was that the boy had recovered physically and was responding well to psychological treatment: “Ben is doing very well, he is very strong and brave and he is so sweet – like a piece of love,” she said.

“He doesn’t feel lonely, he knows that we will support him and that we are his family (now). He talks about his mum and dad from time to time, but we have a very strong and close family, and we will give to Ben the same love that Susana and Darren gave him.”

POSTSCRIPT: Living with Fragile X: Cynthia and Daniel

Daniel announces his presence long before he sidles into the room – a succession of ear-splitting roars, imitating the Disney cartoon lion he likes to watch on his iPad. He has never managed a coherent conversation.

A lanky lad with light brown hair, the only physical sign that he has Fragile X syndrome is his characteristic elongated face and ears – that and his habit of walking precariously on tip-toes, of avoiding eye contact, and the way in which his limbs occasionally give an involuntary jerk.

Cynthia Roberts, a capable woman in her mid-50s, is his mother and she has been looking after him for 22 years. It cost her her first marriage – or, at least it contributed to its breakdown – and she needs to take anti-depressant drugs to cope with the daily burden of care.

She tells me her story sitting in the lounge-room of her house in the western Sydney suburb of Burwood Heights while Daniel, beside her on the couch, plays with his iPad and gives an occasional roar.

I feel slightly nervous, especially when I learn that Daniel had been “expelled” on his first day at Ashfield Public School after biting a teacher’s aide.

Cynthia had no idea when she and her then-husband Colin decided to have children in 1984 that she was a Fragile X carrier. In fact, she had never heard of it, which is richly ironic because she works for Genea, a Sydney IVF company which organises genetic screening to detect the condition.

Their first child was a girl, their daughter Amy, a “normal” child with none of the symptoms of Fragile X. Ten years later she fell pregnant again, and this time it was twins, Daniel and Rachel.

They did notice that Daniel was slower than his sister in reaching his milestones—he was slower to start crawling, he didn’t walk until he was two, and he was still not properly toilet-trained at five. However their GP, who evidently had not heard of Fragile X, told them not to worry.

Eventually they were referred to a pediatrician who recommended a battery of tests, and Daniel was diagnosed with Fragile X. Says Cynthia:

“I was devastated… I felt as though my heart had been ripped out of my chest. I knew nothing about it, and the more I read the worse I felt. I was reading about a boy who still needed toilet training at 11.”

As well as his intellectual disability, Daniel was prone to epileptic seizures – in the early days this required hospitalisation – and he was diagnosed with depression, ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and a range of other conditions. These days, however, as long as he is kept on a regime of five different drugs, taken twice a day, things are under control, apart from the occasional “bathroom accident.”

Because of his behaviour his activities are limited. “Normal” school is out since the biting episode – he goes to a special school for the intellectually disabled – and so is the cinema, after patrons complained about the noise he made. But Daniel does manage a few outings, and he enjoys a weekly dance class for the disabled at Concorde called Dancing Hearts.

As she approaches retirement, Cynthia has two things on her mind. Amy has inherited the faulty Fragile X gene – although she has no symptoms – and will have to think about using IVF, screening the embryos for Fragile X before implantation, if she wants to have children.

And that does not come cheap. It costs about $3000 to screen each batch of embryos. Cynthia and Genea have been campaigning for years to have this covered by Medicare, arguing that the price would be far outweighed by the cost to society of bringing another Daniel into the world.

And she would like to be confident of Daniel’s future after she dies. She doesn’t want to leave that burden to her daughters – although she knows they would accept the responsibility – and would like to see him in supported living accommodation.

As I leave, he gives another loud, parting roar.

Publishing Info

Pub: SBS Online

Pub date: February 2017

Support

If you’re suffering from mental health issues and need immediate support, contact:

Lifeline 13 11 14

Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636

MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78

The Fragile X Association of Australia’s helpline is 1300 394 636. Further information is at the association’s website.